Designing A Simple DUIM Application¶

Introduction¶

The next few chapters of the manual introduce you to some of the most important DUIM concepts, and show you how to go about designing and implementing a simple DUIM application. On a first read through, you should work through each chapter in turn, since each chapter relies heavily on the information in the previous chapters.

Design of the application¶

For the purposes of this example, the application developed is a simple task list manager. The design of the application attempts to achieve the following goals:

The design is simple enough that the principles of the programming model should not be obscured by the code itself.

The design attempts to use the most common elements of the various DUIM libraries.

The design is extensible, so that you can customize it to your own needs.

A task list manager was chosen because it is representative of the sort of GUI application that you will probably want to develop. Although the overall design is quite simple, it demonstrates several commonly used elements and techniques, and is easily extensible beyond the scope of this manual, should you wish to experiment with the code. The concept of a task list manager is familiar to the majority of readers, so you can study the code and the programming model, without having to spend time figuring out what the application itself is supposed to do.

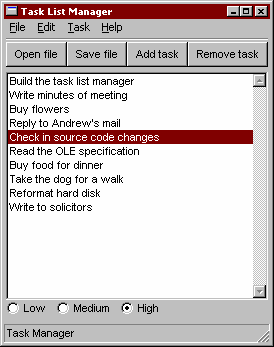

The final task list manager is shown in Designing A Simple DUIM Application. To load the code for the final design into the environment, choose Tools > Open Example Project from any window in the environment, and load the Task List 1 project from the Documentation category of the Open Example Project dialog.

The Task List Manager Application¶

The task list manager is very simple to use. You create a list of things that you need to do, assigning a priority to each task as you create it. The application can display the tasks in your list sorted in a variety of ways. You can save your task list to a file on disk, and open files of the same type.

The task list manager demonstrates the use of menus and a variety of button, list, and text controls.

Creating the basic sheet hierarchy¶

This section shows you how to create gadgets and sheets that make up the overall visual design of the interface. It shows you how to improve upon an initial design, but does not go into any details on the callbacks necessary for the application; at the end of this section you have an initial visual design.

Placing all the elements in a single layout¶

The main part of the task list manager is a list box that is used for displaying the tasks that you add in the course of using the program. For the initial design, there are buttons that let you add and remove tasks from the list, and a text field into which you type the text for new tasks.

To begin with, the following code creates all these elements, and places them in a single window, one above the other.

make(<column-layout>,

children: vector (make (<list-box>, items: #(), lines:15),

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:"),

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task"),

make (<push-button>,

label: "Remove task")));

You might notice a number of problems with this initial design:

Firstly, the items have all been created correctly, but the resulting window is not particularly attractive. In order to improve the appearance, you need to rearrange the elements in the window by making better use of the layout facilities provided by DUIM.

Secondly, the application does not yet look very much like a typical Windows application. Rather than individual buttons, the application should have a tool bar, and it is not common to have a text field in the main window of an application. There is no menu bar. Currently, the application has more of the feel of a dialog box, than a main application window. These issues are addressed later on in the example.

Redesigning the layout¶

To address the issue of layout first, you should group the text field and the Add task button in a row; since the two elements are inherently connected (the task you add is the one whose text is displayed in the text field), it makes sense to group them visually as well.

The following code creates the necessary row layout:

horizontally ()

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:");

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task");

end

Note that the macro horizontally has been used here. This macro takes

any expressions that are passed to it and creates a row layout from the

results of evaluating those expressions. The macro vertically works in

a similar way, creating a column layout from its arguments. Use

vertically to combine the row layout you just created with the Remove

task button that still needs to be incorporated:

vertically ()

horizontally ()

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:");

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task");

end;

make (<push-button>, label: "Remove task");

end

Finally, you need to add this sheet hierarchy to another row layout, so that the main list box for the application is on the left, and the sheet hierarchy containing the buttons and text field is on the right:

horizontally ()

make (<list-box>, items: #(), lines: 15);

vertically ()

horizontally ()

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:");

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task");

end;

make (<push-button>, label: "Remove task");

end;

end

In the last few steps, you have exclusively used horizontally and

vertically. In fact, it does not matter if you use these macros, or

if you create instances of <row-layout> and <column-layout>

explicitly using make.

Note

You may have to resize the window to see everything.

Adding a radio box¶

There is one aspect of the initial design that you have not yet incorporated into the structure: the radio box. This serves two purposes in the application:

It lets you choose the priority for a new task.

It displays the priority of any task selected in the list.

The code to create the radio box is as follows:

make (<radio-box>, label: "Priority:",

items: #("High", "Medium", "Low"),

orientation: #"vertical");

Notice that the orientation: init-keyword can be used to ensure that

each item is displayed one above the other.

It is probably best to place the radio box immediately below the Remove

task button. To do this, you need to add the definition for the radio

box at the appropriate position in the call to vertically.

(horizontally ()

make (<list-box>, items: #(), lines: 15);

vertically ()

horizontally ()

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:");

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task");

end;

make (<push-button>, label: "Remove task");

make (<radio-box>, label: "Priority:",

items: #("High", "Medium", "Low"),

orientation: #"vertical");

end);

Using contain to run examples interactively¶

You can use the function contain to run any of the examples above

using the interactor available in the Dylan environment. This function

lets you see the results of your work immediately, without the need to

compile any source code or build a project, and is extremely useful for

experimenting interactively when you are developing your initial ideas

for a GUI design.

The contain function takes any expression that describes a hierarchy

of sheets as an argument. It creates a frame which contains this sheet

hierarchy, and displays the resulting frame on the screen.

Thus, to run any of the code segments shown in this chapter, simply pass

them to contain as an argument. Here are two examples, adapted from

earlier examples in this chapter, as illustrations of how to use

contain.

contain (horizontally ()

make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:");

make (<push-button>, label: "Add task");

end);

contain (make (<text-field>, label: "Task text:"));

At this point, take a few minutes to go back over this chapter and

practice using contain to run the code fragments that have already

been discussed.